You’ve hit a brick wall. You’ve found an ancestor on a census, but their life that brought them to that point is a complete mystery. You have a name, maybe a place, and not much else. This is exactly where I found myself with my second great-grandmother, Annie.

I knew my great-grandfather Henry was born to Annie in Ayrshire in 1881, but was brought up and lived in Lanarkshire. A likely birth record showed his father, John, was already deceased when he was born, which raised puzzling questions about why the family had moved and whether I had the right person.

That’s when I discovered poor law records. They can sound intimidating, and the name itself suggests a sad chapter in history. But what I found was a rich, detailed, and moving account of my ancestor’s life that answered all my questions. These records transformed Annie from a mysterious figure into a real person facing genuine tragedy and making difficult decisions for her family’s survival.

If you’re new to genealogy, poor law records might be an unfamiliar but incredibly powerful research tool. They often contain detailed information about families during their most vulnerable moments, filling gaps that census records and certificates can’t bridge. While other sources give us snapshots, poor law records reveal the human stories behind the statistics.

What are poor law records and why do they matter for genealogy?

Poor law records are documents created by the system that supported destitute people in Britain from the 16th century until the early 20th century. Before the modern welfare state, local parishes and later Poor Law Unions were responsible for helping those who couldn’t support themselves.

The system worked differently across Britain. In England and Wales, the Old Poor Law before 1834 varied from parish to parish – some were generous, others harsh. The New Poor Law of 1834 introduced a much stricter system designed to discourage people from seeking help by making workhouse conditions deliberately unpleasant.

Scotland had its own approach. Before 1845, poor relief was managed by Kirk Sessions (local church courts) and heritors (landowners), funded mainly through church collections. They helped the “deserving poor”, those unable to work due to age, sickness, or being orphaned. The Poor Law Scotland Act of 1845 created Parochial Boards in each parish, leading to much more detailed record-keeping.

These records matter enormously for genealogy because they document people who might not appear prominently elsewhere. Working-class families, agricultural labourers, widows, and single mothers feature heavily, giving us insights into lives that might otherwise be invisible to history.

The different types of poor law records and what they contain

Understanding the various types of poor law records helps you know what stories they might tell and where to focus your research efforts.

Workhouse and poorhouse admission and discharge registers

These are perhaps the most common and accessible records you’ll find. These books recorded everyone who entered or left these institutions, often including their age, place of birth, occupation, and reason for admission. People often moved in and out multiple times as circumstances changed, so you might find several entries for the same person.

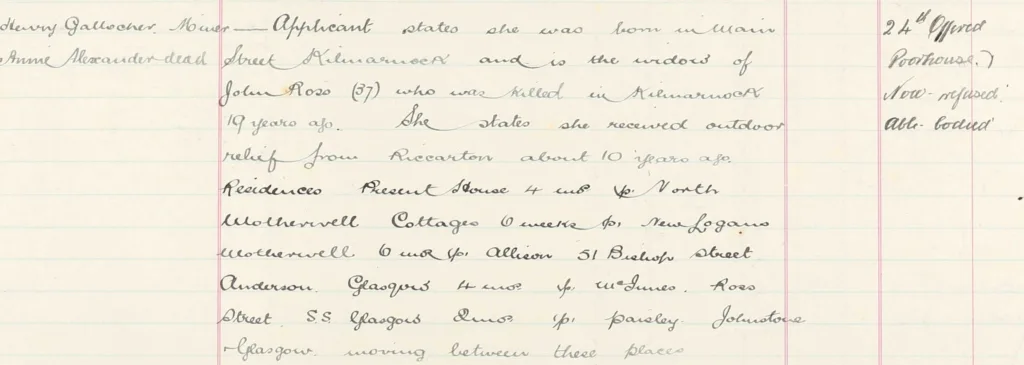

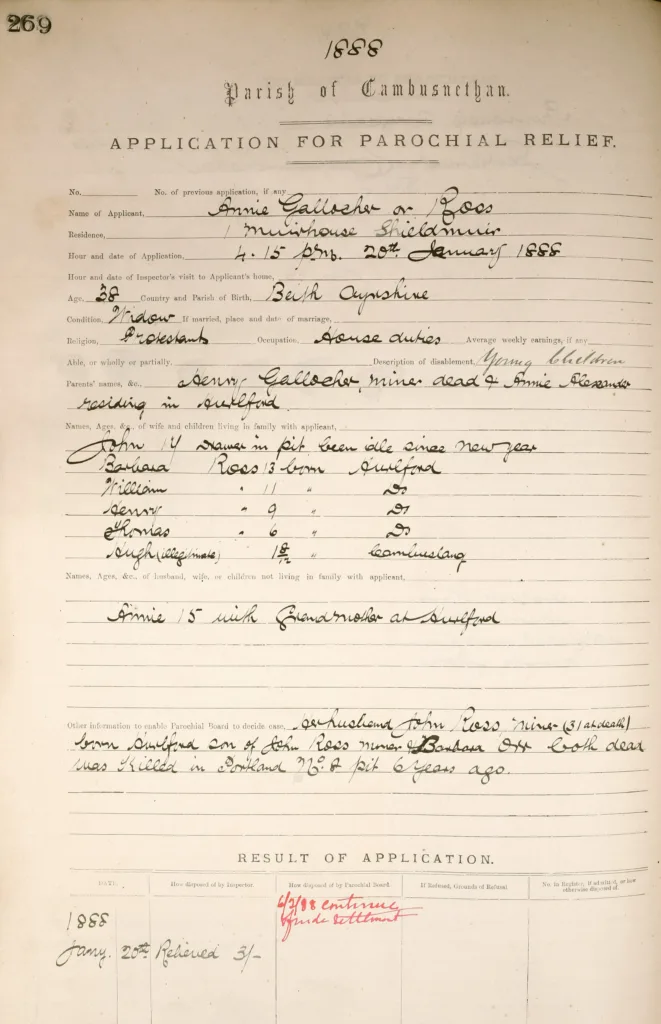

For my ancestor Annie, poor law records provided multiple breakthroughs. The key discovery came from her 1888 application for relief made in Cambusnethan, Lanarkshire. This document confirmed that John was indeed Henry’s father, but revealed the tragic circumstances. John had died in a mine accident in Ayrshire while Annie was pregnant with Henry. A later application for poor relief from 1904 confirmed these same facts, giving me confidence in the story.

Settlement records and certificates

These documents dealt with determining which parish was legally responsible for supporting someone if they became destitute. These can be goldmines for genealogists because they often trace family movements and include sworn statements about where people were born, married, or had lived and worked. They reveal migration patterns and can help you break through geographic brick walls.

Board of guardians minutes and parochial board records

This type of record documents the meetings of local officials who administered poor relief. These detailed minutes record decisions about individual cases – who would be admitted to the workhouse, who would receive outdoor relief (support without entering the workhouse), and who might be apprenticed to learn a trade. These records often work alongside formal applications to provide the complete picture of a family’s circumstances.

What makes Scottish poor relief records special for genealogy

Before 1845, poor relief was managed by the Kirk Sessions (the local church courts) and heritors (local landowners). They collected funds, often from church collections, and distributed them to the “deserving poor”, those who were unable to work due to old age, sickness, or being orphaned. The records from this period can be found in Kirk Session minutes, which sometimes name the individuals who received relief.

See: The Kirk Sessions and the Poor (Scotland’s People)

The Poor Law (Scotland) Act of 1845 brought significant changes. It created Parochial Boards in each parish to manage poor relief, and a central Board of Supervision in Edinburgh to oversee the system. This new system led to the creation of more detailed records, which are a goldmine for genealogists.

Scottish poor relief records are incredibly detailed and often more informative than their English counterparts. When someone applied for relief in Scotland, an Inspector of the Poor would visit them and create comprehensive records of their circumstances.

These Scottish records typically include family details like the names and ages of the applicant, their spouse, children, and even parents. This is particularly valuable for finding illegitimate ancestors, as fathers’ names are often recorded. You’ll frequently find specific birthplaces rather than just vague references like “Scotland” or “Ireland” that appear in census records.

The records also trace residence history, listing where people lived over several years, and explain exactly why relief was needed – death of a spouse, illness, disability, or unemployment. Sometimes you’ll even find details about housing conditions, medical status, and religious denomination. This level of detail exists because authorities needed to determine someone’s parish of settlement, which parish was legally responsible for them.

Scottish poorhouses operated differently from English workhouses too. They were generally intended for the sick, disabled, or elderly rather than as deterrents for able-bodied poor people. While still a last resort, conditions weren’t as deliberately punitive as in the English system.

Where to find poor law records for your family research

The key to finding poor law records is understanding that they were created and kept locally, so you need to know where your ancestors lived to track down the right archives.

Local record offices remain the primary repositories. Each county record office typically holds records for Poor Law Unions in their area, while city archives often have urban workhouse records. Start by searching online for your area’s record office, as most now have online catalogues you can search using terms like “poor law,” “workhouse,” or “board of guardians.”

Online databases have revolutionized access to these records. Ancestry has extensive collections of workhouse records, particularly admission and discharge registers. Findmypast holds significant collections, especially for London areas. FamilySearch offers many records for free, including some Scottish collections that are harder to find elsewhere.

The National Archives in London holds some centralised records, particularly policy documents and correspondence. Their online Discovery catalogue can help identify relevant collections, though day-to-day operational records usually remain in local archives.

Don’t overlook local family history societies. Many have transcribed or indexed poor law records for their areas. Their volunteers often have intimate knowledge of local collections and can point you toward resources you might miss otherwise.

For Scottish records, Scotland’s People is the official government source, while local archives like Glasgow City Archives and Edinburgh City Archives hold extensive poor law collections.

How I uncovered Annie’s story through multiple record types

My research into Annie demonstrates how poor law records work alongside other sources to solve genealogical mysteries.

The breakthrough came from Annie’s 1888 application for poor relief in Lanarkshire. This document didn’t just confirm that John Ross was Henry’s father; it revealed the tragedy behind the family’s circumstances. John had died in a mine accident in Ayrshire while Annie was pregnant with Henry. Suddenly, the geographic puzzle made sense: Annie had moved from Ayrshire to Lanarkshire as a pregnant widow, likely seeking family support or work opportunities.

A second poor relief application from 1904 confirmed these same details, giving me confidence that this wasn’t a clerical error but the genuine family story. To verify the mining accident, I searched mining records for the period and found evidence of John’s death, providing independent confirmation of the poor law records.

Want to learn more about the hardships of life as a miner in the 18th and 19th centuries? See our article about Unearthing Scotland’s hidden history of servitude.

Beginners TIP

Working backwards from the poor law discoveries, the key facts from other records fell into place. Henry’s 1881 birth record confirmed his father was deceased at the time of birth. The 1869 marriage record showed John and Annie’s wedding in Ayrshire, while census records from 1861 and 1871 confirmed them living there with John working as a miner.

Moving forward from the Poor Law records to the post-1891 census records showed Annie, Henry, and his siblings settled and working in Lanarkshire. Subsequent census and Poor Law records show that mining remained the key employment for the family as Henry and his brother both became miners in Lanarkshire.

This research revealed Annie as a remarkably strong woman who faced devastating loss and managed to relocate her family, find work, and build a new life. Despite John’s death in the mines, the family couldn’t escape the mines, with his sons’ employment showing how few options people had in those times. The poor law records provided the emotional and practical context that other sources couldn’t offer.

Practical tips for searching and interpreting poor law records

Searching these records effectively requires understanding their unique organizational systems and terminology. Start with what you know – poor law records are organized geographically, so knowing where your ancestors lived is crucial. If you’re unsure which Poor Law Union covered their area, search online for the place name plus “Poor Law Union” or consult a historical gazetteer.

Be flexible with dates and don’t limit searches to specific years. People often used the poor law system multiple times throughout their lives, entering and leaving as circumstances changed. Cast your net wide as someone might appear in records several years before or after other events you know about.

Expect variant spellings of both surnames and places. Record keepers weren’t always careful about spelling, and people might have given their names differently depending on their accent or literacy. Search for phonetic spellings and common variations. I found Annie under ‘Gallocher’ and ‘Gallocher’.

Understanding the terminology is crucial. Terms like “relieved,” “removed,” or “absconded” have specific meanings in poor law contexts. “Outdoor relief” meant support given to people living in the community rather than in institutions. “Settlement” referred to which parish was legally responsible for someone, not necessarily where they chose to live.

What these records reveal about our ancestors’ real lives

Poor law records offer more than genealogical facts; they provide windows into how ordinary people lived, worked, and survived. The records can illuminate women’s experiences in unique ways. Widows, unmarried mothers, and elderly women feature prominently, showing both their vulnerabilities and resourcefulness. Many women used workhouses for childbirth or during illness, then returned to independent living once they recovered.

For some children, poor law records often provide the only detailed information about their early years. Apprenticeship arrangements, school placements, and family separations are all documented, giving us insights into childhood experiences that rarely appear in other sources.

Preparing yourself emotionally for poor law research

I need to offer a word of caution here. Poor law records can be emotionally challenging to read. They describe desperate situations, family separations, and immense hardship. Annie’s story includes moments that were difficult to discover, times when her family was split up, when impossible choices were made, when poverty pushed children towards the same deathly fate as their father.

But these records also reveal something profound about our ancestors’ strength and perseverance. They show ordinary people facing extraordinary challenges and finding ways to survive and rebuild. Annie’s story isn’t just about poverty; it’s about resilience, about a woman who uses temporary support to create a foundation for her future family. And of course, if it wasn’t for this resilience, we wouldn’t even be here.

Don’t be afraid to explore these records. Yes, you might discover difficult truths about your ancestors’ lives, but you’ll also discover their humanity, their strength, and their determination to survive against the odds. A testament to the courage of ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances.

Be prepared to spend time digging through different types of records, but know that the reward can transform your understanding of your family’s story. Poor law records might just be the key that unlocks a whole new chapter in your ancestors’ lives, one filled with real human struggles, triumphs, and the unbreakable determination to keep going.