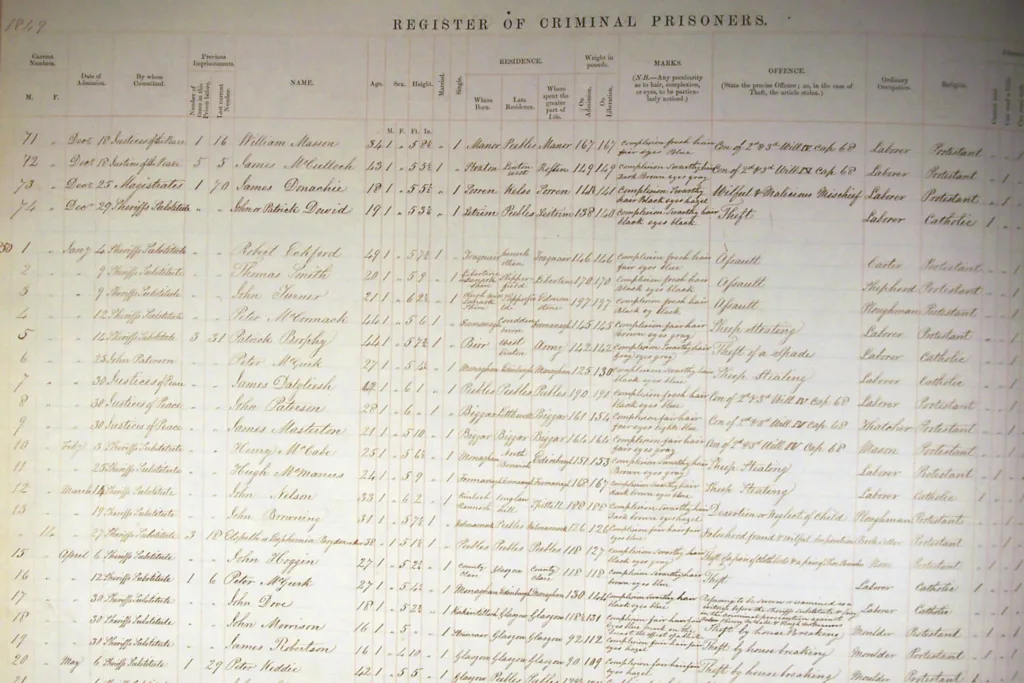

If you’ve ever searched the census and noticed a missing ancestor, or discovered one listed in an unexpected place, you might have come across a prison record without even realising it.

Census records include people in all sorts of institutions: workhouses, asylums, ships, and yes, prisons. Finding a prisoner in your family tree can be surprising, emotional, or just plain puzzling. But it’s also an important part of their story, and the census might be the first clue.

In this guide, we’ll walk through how prisoners appear in UK census records, how to identify them, and what to do next if you find one.

Were prisoners included in the UK census?

From the very first censuses, prisoners were counted just like everyone else. Each person in a prison on census night was recorded where they were staying, even if it wasn’t their usual home.

This means you might find:

- Someone listed under their initials (especially in later years)

- A relative not living at home, but in a prison or other institution

- A separate census schedule for the prison itself, listing dozens or even hundreds of inmates

Every UK census from 1841 to 1921 includes prisoners, though how much information was recorded varies over time.

How do you spot a prisoner in a census record?

It’s not always obvious at first glance, especially for beginners. Here’s what to look out for:

- Location: The person is listed in an institution with a name like “HM Prison” or “County Gaol”

- Relationship: They are marked as “prisoner” in the relationship column

- Occupation: This may be blank, or still list their trade (e.g. labourer, miner, shoemaker)

- Initials: In some later censuses (notably 1911), prisoners were recorded by initials only, not full names, to protect privacy

- Birthplace: This can help you confirm if the person is your ancestor, even when names are limited

If you can’t find someone at home in a census, try searching for them by age and birthplace, without a location filter. You might discover them listed in an unexpected place.

Why might someone be in prison?

There are many reasons someone could appear in prison records. It might be a short sentence for a minor offence, time spent on remand awaiting trial, or a longer stay for a more serious crime.

These were often punished with short-term imprisonment, especially for working-class men and women in the 19th century. Remember, times were very different—and the social safety net we know today didn’t exist.

What can you learn from a census record about a prisoner?

Census records won’t give you details of the crime or the sentence, but they will tell you:

- That the person was in prison at a specific place and time

- Their likely identity (even if only initials)

- Who else was imprisoned there (sometimes giving clues about shared events)

This can act as a springboard for further research in prison registers, criminal records, or newspaper archives, where you might find trial reports or arrest notices.

Where can I go next if I find a prisoner?

If a census record reveals a prisoner in your family, you can look deeper using:

- Prison registers (available on sites like Ancestry, Findmypast, and at local archives)

- Court records (especially Sheriff Court or Quarter Sessions)

- Newspapers (many minor cases were reported in local papers)

- Old Bailey Online (for London cases before 1913)

- National Records of Scotland or The National Archives (UK) for further leads

Check out Scottish Indexes website for access to Scotland’s Criminal Database with over 800,000 Scottish criminal records including Scottish court and prison records.

See: Scottish Indexes

PRO TIP

It may take some digging, but this part of your family story can reveal context, hardship, resilience, or even redemption. Every record adds depth to the bigger picture.

Finding a prisoner in the census might feel surprising, but it’s not unusual. These records remind us that our ancestors were real people, living in complex times and facing all kinds of challenges.

Whether it’s a brief line in the 1881 census or a mystery solved by tracing initials in 1911, discovering this kind of history can actually bring your research to life.