Every family history researcher hits a frustrating point when a record, a person, or an entire branch of the family tree seems to vanish without explanation. You’ve checked the census, searched birth records, followed every name trail and then… nothing.

This moment is so common that there’s a name for it: a genealogy “brick wall.”

If you’re just starting out and have run into one, you’re not alone. In fact, dealing with brick walls is a normal part of the process. This article will explain what a brick wall is, why they happen, and what you can do to break through step by step.

What does ‘brick wall’ mean in genealogy?

A brick wall in genealogy is a point in your research where you can’t find any further information about a person or family line. It feels like you’ve hit a dead end. No birth record. No census entry. No marriage.

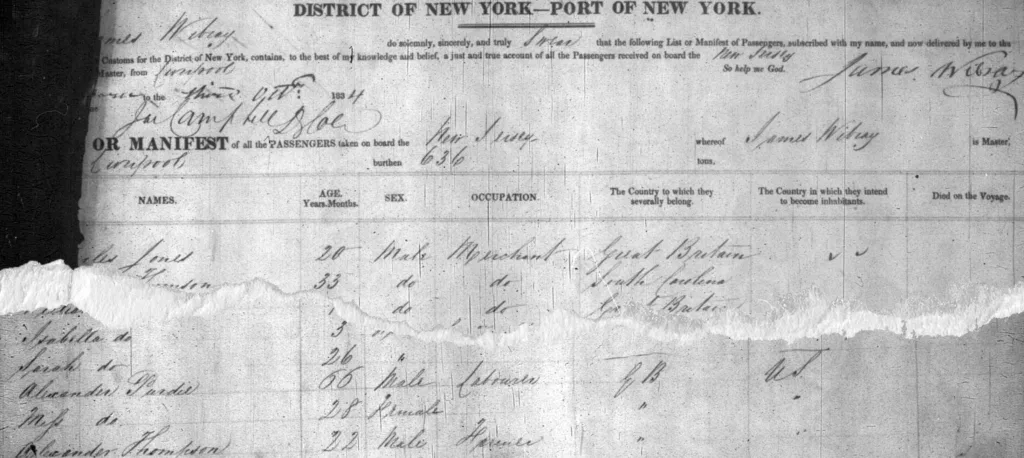

This can happen with any ancestor, but especially those born before civil registration (which began in Scotland in 1855, for example), those who emigrated, or people with common names. Sometimes it’s simply because the records were never created, got damaged, or haven’t been digitised yet.

The good news? Most brick walls can be chipped away with fresh ideas and a bit of patience.

How do brick walls happen?

Understanding the root causes helps you plan your next move. Common reasons include:

- Missing records: Many historical records have been lost, destroyed, or never existed in the first place.

- Name changes or variations: Spelling wasn’t standardised until recently, and names were often written phonetically.

- Migration: Ancestors may have moved town, county, or country without leaving clear clues.

- Illegibility: Handwriting in old records can be difficult to read or index correctly leading to errors.

- Assumptions: Sometimes we go down the wrong path because we assume a fact (like a birth year or location) that isn’t quite right.

Once you recognise the problem, it becomes easier to choose the right tool or tactic.

Before you panic: check the basics again

It’s worth revisiting what you already know. Brick walls can sometimes be self-made by overlooking something simple.

Try this checklist:

- Double-check spelling variations (e.g. McDonald, MacDonald, MacDonell)

- Look at wider date ranges (if you’re searching 1850–1860, try 1845–1870)

- Confirm your sources. Are they transcriptions or images of originals?

- Review your research log or notes. Did you forget to search a nearby parish or county?

Sometimes a break and a second look is all it takes to spot what you missed the first time.

Broaden your search

If the usual approach isn’t working, try casting a wider net.

- Search neighbouring areas: People often married or moved just across parish or county lines.

- Explore lesser-used record sets: Valuation rolls, school records, poor law applications, or directories might offer a clue.

- Use wildcard searches: Most search tools let you substitute a * for unknown letters. Searching “McD*nald” will catch McDonald, MacDonald, and more.

- Reverse the focus: Can you find a sibling, child, or spouse instead? Tracing relatives might reveal your missing person.

If you’ve only been using one or two sites, it might be time to try others or even local archive websites are great places to start.

Use timelines to spot gaps

Creating a timeline for your ancestor can help you spot missing pieces or unrealistic assumptions. Jot down everything you know, in order.

Example:

- 1842 – Born in County Antrim (source: 1901 census)

- 1861 – Married in Glasgow

- 1871–1901 – Appears in every Scottish census

- 1910 – Died in Lanarkshire

Here, a big gap jumps out: What happened between 1842 and 1861? Did the person come to Scotland as a child or as a young adult? Is there a migration record? A sibling who made the journey too?

Timelines also help with matching up multiple people of the same name. If one John Kelly was in Ireland in 1860, and another was in Greenock, they’re unlikely to be the same man.

Try a different angle: creative problem solving

Sometimes solving a brick wall is about looking at the question sideways.

- Look for newspaper archives: Local papers often included notices for births, marriages, deaths, or even small news stories.

- Check poor relief or workhouse records: If your ancestor was struggling, they may appear in records kept by local authorities or churches.

- Study maps: Places, parishes, and boundaries changed over time. Knowing the geography can explain record gaps.

You can also try talking through the puzzle with someone else. Often another pair of eyes can bring new insight. Online forums, Facebook groups, or even genealogy clubs are often full of friendly folks who’ve been there too.

Know when to pause

Some brick walls don’t break right away. Taking a break doesn’t mean giving up. New records are added online all the time. What seems impossible now might be solvable in a year.

You can set the problem aside and work on a different branch for a while. Or focus on writing up what you do know, turning it into a story for your family.

See: Storytelling

Keep a research log

One of the best tools for avoiding brick wall frustration is a simple research log. It helps you:

- Track where you’ve looked

- Avoid repeating searches

- Note ideas for next time

It doesn’t have to be fancy. Even a notebook or spreadsheet can do the job.

Persistence pays off

Every family tree has at least one mystery. Whether it’s a vanished great-grandfather, an illegitimate birth, or a trail that leads across the ocean, these brick walls are part of the adventure.

Sometimes the answer is hiding in plain sight. Sometimes it takes creativity, time, or luck. But even if you never solve it completely, you’ll learn more about history, records, and your family along the way.