When you think about your Scottish ancestors, you probably imagine hardworking people in bustling communities. But did you know that many miners and salt workers in Scotland lived under a system that tied them to their work, almost like property, well into the late 18th century?

As you piece together the lives of your Scottish ancestors, you might stumble upon a surprising and often overlooked chapter of history: a system of servitude that bound thousands of workers and their families. Being bought, sold, and inherited along with a mine wasn’t some ancient relic, but a reality for many just a few generations ago.

This article will help you understand the challenging lives of these “slaves of the soil,” as author Sir Walter Scott described them.

The surprising truth about Scottish indentured labour

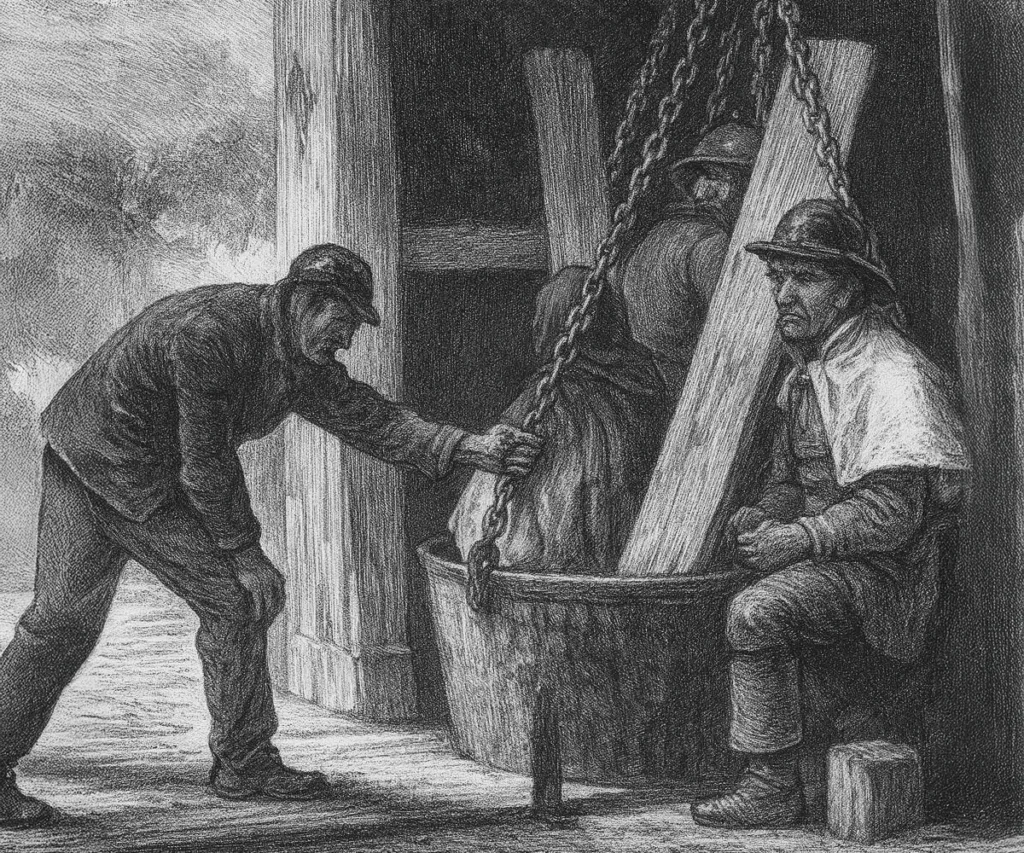

When we think of slavery, images of distant lands often come to mind. But Scotland had its distinct form of bondage, particularly affecting colliers (coal miners), coal-bearers (who carried coal from the face to the pit-mouth), and salters (salt workers), along with their families. These individuals were fixed to the soil, meaning they were tied to the coal mines or salt works where they laboured. They could be, and often were, bought, sold, and inherited as part of the mining or salt-making property itself. Your ancestor could be listed in a sale document, right alongside the mining equipment, with their value even detailed separately.

This system arose because coal and salt were incredibly important to Scotland’s economy. Salt-making, often found along Scotland’s extensive coastline, was a massive industry that required huge amounts of coal to heat the seawater in vast pans. This close connection meant that the same laws that bound colliers also applied to salters. The work was hard, dangerous, and dirty, and few people wanted to do it freely. To ensure a steady supply of labour, a system of legal and social control emerged that effectively enslaved these workers.

The daily grind of bound workers

The lives of colliers and salters were marked by a profound lack of personal liberty. If your ancestor was one of them, their daily existence was dictated by their master and the mine.

Work and family life

Once bound to a coal works, they were expected to work there for life, and this often extended to their families too.

While not strictly born into servitude, their children would often become bound if they followed the occupation, which was common due to their parents’ inability to afford other training. Coal-masters encouraged this by giving “arles” (gifts or tokens, sometimes even a pair of shoes) at a child’s birth or baptism, sealing their future service to the mine.

The work was severe, dangerous, and dirty. Miners and their families were often ridiculed for their “black, frightful appearance” after a shift.

They were expected to work six days a week, with Christmas as the only exception. Missing a day could result in a fine of twenty shillings Scots (a significant sum) or even physical punishment.

Despite their bound status, they weren’t entirely stripped of all rights. They could acquire personal and real estate and marry at will. Interestingly, if a collier girl married a free man, she could become free herself. In a surprising 1747 case, a court even ruled that a bound collier could be a counsellor in a Royal Burgh and vote in parliamentary elections, suggesting a sliver of civic participation. However, this stood in stark contrast to their exclusion from the 1701 “Scotch Habeas Corpus Act,” which protected other citizens from wrongful imprisonment. Their coal masters could also transfer them between different coal works, making them more like property than “tied to the land”.

Methods of suppression

The servitude of Scottish colliers and salters was backed by specific laws and legal interpretations that made escape almost impossible.

In 1606, an Act of Scottish Parliament was the cornerstone of this system. It stated that no one could hire a collier or salter without a testimonial (a kind of permission slip) from their previous master. If an employer hired someone without this, they had to return the worker within 24 hours if challenged, or face a penalty of £100 Scots (around £15,000 today). Crucially, these testimonials were rarely granted, effectively binding workers for life. If a collier tried to leave or received wages from a new master, they could be treated as thieves and physically punished.

Judicial interpretations and forced labour

Over time, judges, eager to ensure a steady supply of coal for the nation, interpreted these laws in ways that further solidified the masters’ control. A key legal fiction emerged: working “Year and Day” (a year and a day) at a coal-work was deemed to bind a collier for life, even if they hadn’t explicitly agreed to it. Court decisions consistently favoured masters, allowing them to reclaim runaways even after several years. The laws also empowered masters to apprehend “vagabonds and sturdy beggars” and force them to work in coal-heughs or salt-pans, adding to the captive labour pool.

The Truck system

Even after legal emancipation, another system of control, the Truck System, heavily influenced miners’ lives, particularly in the 19th century. This involved workers being paid partly in goods or forced to spend their wages at company-owned stores. Often, cash advances came with a “poundage” deduction (a fee for the advance) or the condition that most of the money be spent at the company shop. Blacklists of “slopers” (those who didn’t use the company store) were common, and men faced threats of dismissal, or actual dismissal, for not complying.

This system, which also often required workers to rent company housing, kept many families in a cycle of debt and limited their ability to seek better opportunities. An 1871 report examined the prevalence and impact of this practice, which was particularly widespread in the west of Scotland, especially in Lanarkshire and Ayrshire.

See: Report on the Truck System (1871)

See: Truck Shops (NL Council Museums Collections)

A system of exploitation and profit

The primary beneficiaries of this system were the coal-masters and salt-masters, who gained a stable, captive labour force for their incredibly demanding and dangerous industries. This system guaranteed a continuous supply of hands.

The Scottish economy as a whole also benefited. Coal was essential for domestic heating and industry, and the lucrative salt-making industry, which consumed vast quantities of coal, was vital for trade both within Scotland and abroad. The perceived “scarcity of hands” was a convenient pretext for masters to tighten their control over workers, a situation often supported by lawyers and judges who believed that these essential industries couldn’t otherwise secure enough labour. The salt industry was so profitable (with salt sometimes known as “white gold”) that it was deemed worthwhile to burn fifty tons of coal to produce just three tons of salt.

The road to abolition and freedom

The journey to freedom for Scotland’s colliers and salters was a long one, marked by legal battles and growing awareness.

The memorial for the colliers of Scotland

The anonymously published “Memorial For The Colliers of Scotland” in 1762 argued that the colliers’ slavery had no basis in Scottish law, but was a result of masters’ “encroachments” supported by judges. It forcefully contended that this servitude was inconsistent with British Liberty and against the spirit of Christianity. Importantly, it also argued that the bondage itself was causing the scarcity of colliers, as the fear of enslavement deterred many from entering the trade. The authors aimed to petition the House of Commons, believing that abolishing slavery would actually increase the number of colliers (due to higher wages) and even lower the price of coal.

The emancipation acts

Nearly 70 years after the Act of Union with England, Parliament passed the Colliers and Salters (Scotland) Act of 1775. This act acknowledged the state of slavery among colliers and salters and aimed to free new employees, granting them the benefits of the Habeas Corpus Act. However, it included a significant “grandfather clause” that excluded existing workers from immediate liberation and imposed many conditions for them to gain freedom. Many masters resisted, trying to hold onto workers by giving them money as “debts”.

The system was finally, definitively ended by another Act in 1799. This legislation declared colliers and salters “free from their servitude”. While the initial draft of this bill still contained “shreds of the old bonds,” the growing resistance and collective action of the miners, particularly in Lanarkshire, proved crucial. They raised money, sent representatives to other districts, and successfully campaigned to remove the objectionable clauses. This collective push by the miners themselves was vital in securing their full emancipation.

Economic motivation also played a role in the later acts. The system of slavery was increasingly seen as counterproductive to securing a stable workforce, as miners refused to work, left illegally, or joined the military. Freedom, it was realised, offered a more effective incentive for labour.

The abolition in 1799 meant that by the dawn of the 19th century, Scotland could, at last, truly declare that “There are no slaves at home”. While the legal chains were broken, the fight for better working conditions and safety for miners continued for many decades, with systems like the Truck System persisting long after.

Telling their stories

This chapter of Scottish history means that if your family tree leads you to coal or salt mining communities in Scotland, you might be looking at ancestors who lived under conditions of legal servitude. It adds a layer of resilience and struggle to their stories. Records might be scarce, but understanding the laws and the societal context can help you interpret the clues you find. For example, if you find your ancestor listed as a “collier” or “salter” before 1799, you know they were likely living under this system.

Even after 1799, records mentioning “poundage” or company stores could indicate continued economic control through the Truck System.

This history adds depth to your research and perspective to your family stories. Your ancestors weren’t just names on a page; they were people navigating a world where work, freedom, and survival were deeply connected. Understanding the laws, traditions, and hardships they faced can help you tell richer stories about their lives, adding resilience and humanity to your family tree.