When we begin tracing our family tree, we often start with names, dates, and places. These facts are the building blocks of our ancestral knowledge, but on their own, they can feel lifeless. You may find the details found in BMD records fascinating, but do your friends and family?

How do we go beyond the records to better connect with the people who came before us? How can you enthuse and engage your relatives in family history, making the dry facts come to life?

Blend fact and fiction in your family history

One powerful way is through creative storytelling, combining historical research with imagination to breathe life into our ancestors’ worlds. In this article, I’ll walk you through the exact process I used to create fictional diary entries for one of my ancestors, Thomas Quirk, a 19th-century lighthouse keeper. It’s a method that any family historian can use to turn dry facts into compelling human stories.

Storytelling matters in family history

Storytelling gives our ancestors voice, emotion, and context. It allows us to explore what they might have felt, seen, or feared. It doesn’t replace factual research, it enhances it.

When you creatively reconstruct the past, you can:

- Understand your ancestors’ world through their eyes.

- Share your findings in a way that engages family members.

- Convey family history as a narrative, not just data.

Creative ideas for family history storytelling

Family history storytelling can be anything from a historical novel to a recreated artefact or image that helps give a sense of place. I’ve created photo galleries from the period, written short bios of life events, and used social history data or accounts from the time to paint a picture of their life.

I have even made a podcast series, with each episode focusing on an interesting ancestor or event in their life.

I’ll write future articles explaining how you can create and build ideas using all these storytelling techniques, but today I will focus on one of the simpler ones.

Bringing Thomas Quirk lighthouse keeper to life

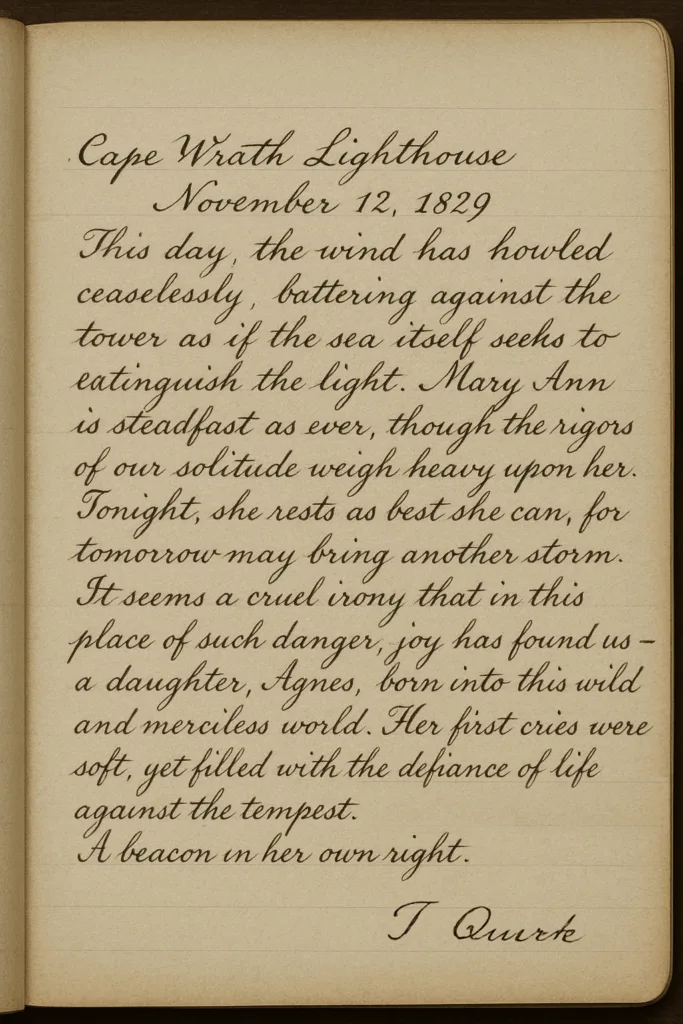

My document research and social history research uncovered a wealth of detail and insight into one of the more unusual careers in my family history.

Thomas’s career began as an assistant lighthouse keeper, travelling the length of the country and ending up as the Superintendent Light Keeper with the Northern Lighthouse Board in Edinburgh. Along the way, his children were born into the life, including his daughter Agnes who was born at Cape Wrath Lighthouse in the very North of Scotland.

My process: from real records to fictional diary pages

The wealth of records from census returns, birth records, Google book searches, and the recently released Light Keepers registers from Scotland’s People already provides layers of context and history. But I wanted to expand and tell a deeper story, a story of that unusual time and place.

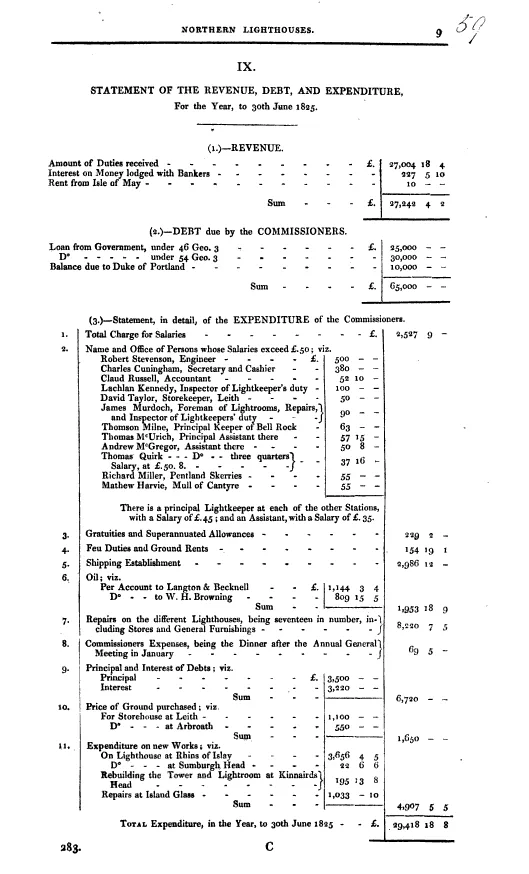

This is one example of how I turned a collection of records into an evocative, fictional diary entry for Thomas Quirk at Cape Wrath Lighthouse in 1829.

1. Start with what you know (factual research)

I gathered the key facts:

- Name: Thomas Quirk

- Birth: Peel, Isle of Man, 1785

- Occupation: Lighthouse keeper from 1814

- Locations: Bell Rock, Cape Wrath, and others

- Life events: Married in Greenock (1828), daughter Agnes born at Cape Wrath

- Death: 1866, Isle of Man

I sourced these from census returns, birth and marriage records, and lighthouse service records from the Northern Lighthouse Board and Scotland’s People.

2. Understand the historical and social context

Next, I researched:

- Daily routines of 19th-century lighthouse keepers

- Weather and working conditions at Cape Wrath and Bell Rock

- Tools and technology (e.g. oil lamps, Fresnel lenses)

- Broader events of the time (e.g. the Industrial Revolution, shipping routes)

Resources included:

- Northern Lighthouse Board history pages

- British Newspaper Archive for social context

- Academic texts on 19th-century maritime Scotland

3. Use your imagination … a little

With facts in place, step into Thomas’s shoes. What would he think or feel as a storm lashed the tower? How might he reflect on his newborn daughter, Agnes? What emotions might isolation stir?

From this, I composed a short fictional diary entry written in period-appropriate language and tone, imagining Thomas recording the birth of his daughter amidst a storm. I tried to keep it believable and historically grounded.

4. Create a tangible output

To help make the story come alive visually, I used AI tools to generate an authentic-looking handwritten diary page. Prompting for aged paper, flowing ink, and all.

Tools used:

- Custom AI image generation (DALL·E via ChatGPT)

- My own research-based narrative writing

This transformed the experience from simple storytelling into a piece of historical fiction that felt tangible and immersive.

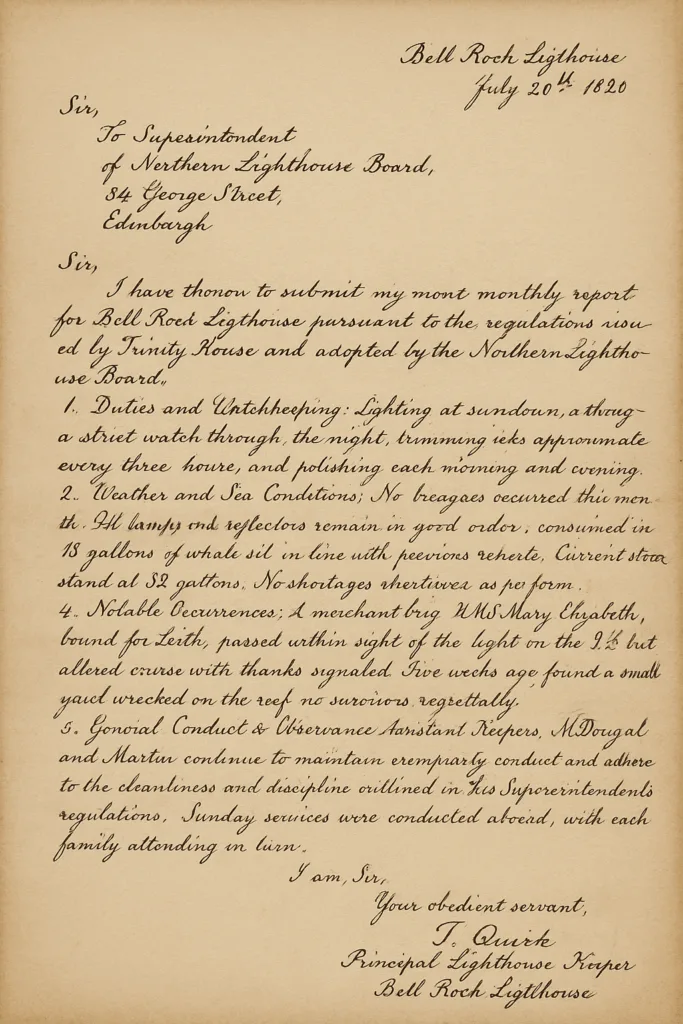

Using similar techniques, I also created a fictional log entry that Thomas might have kept, and a fictional yet historically grounded letter that he could have written in his capacity as a lighthouse keeper, drawing on actual 19th-century lighthouse correspondence and official guidelines.

Although I am still hopeful that the real thing might be out there somewhere in the records!

4. Keep checking the facts, even when fake

However, even with fictional accounts, you should still be checking the details. Below is an initial version of the letter with mistakes, typos and all. This was tidied up for my final version.

Tips for your own family history storytelling

- Choose a strong moment

Pick a meaningful event, birth, migration, war service, or dramatic weather, and imagine it as a lived experience. - Write in the first person

Try letters, diary entries, or interior monologues. This lets you explore thoughts and emotions. - Stick to the emotional truth

Even if you fictionalise events, ground them in the emotional or cultural reality of the time. - Include period detail

Use real historical details, language, customs, and daily routines to enrich the scene. Avoid modern slang or ideas. - Label It clearly

Make it clear to readers that this is a creative reconstruction based on factual research. This builds trust and invites imagination.

Bringing our ancestors to life through storytelling doesn’t dilute history, it strengthens it. When we blend genealogical facts with narrative creativity, we create something powerful: stories that resonate, educate, and endure.

Whether you’re writing for yourself, your family, or a wider audience, consider letting your ancestors speak – not just through dates, but through imagined thoughts, fears, and hopes. It’s in those moments that we can walk through time with them.